I was first introduced to TENS by physical therapists during my training. They made it sound like a wonderful way to relieve pain, and I was expecting to hear more about it. As the years passed, I heard it mentioned less and less. I wondered why.

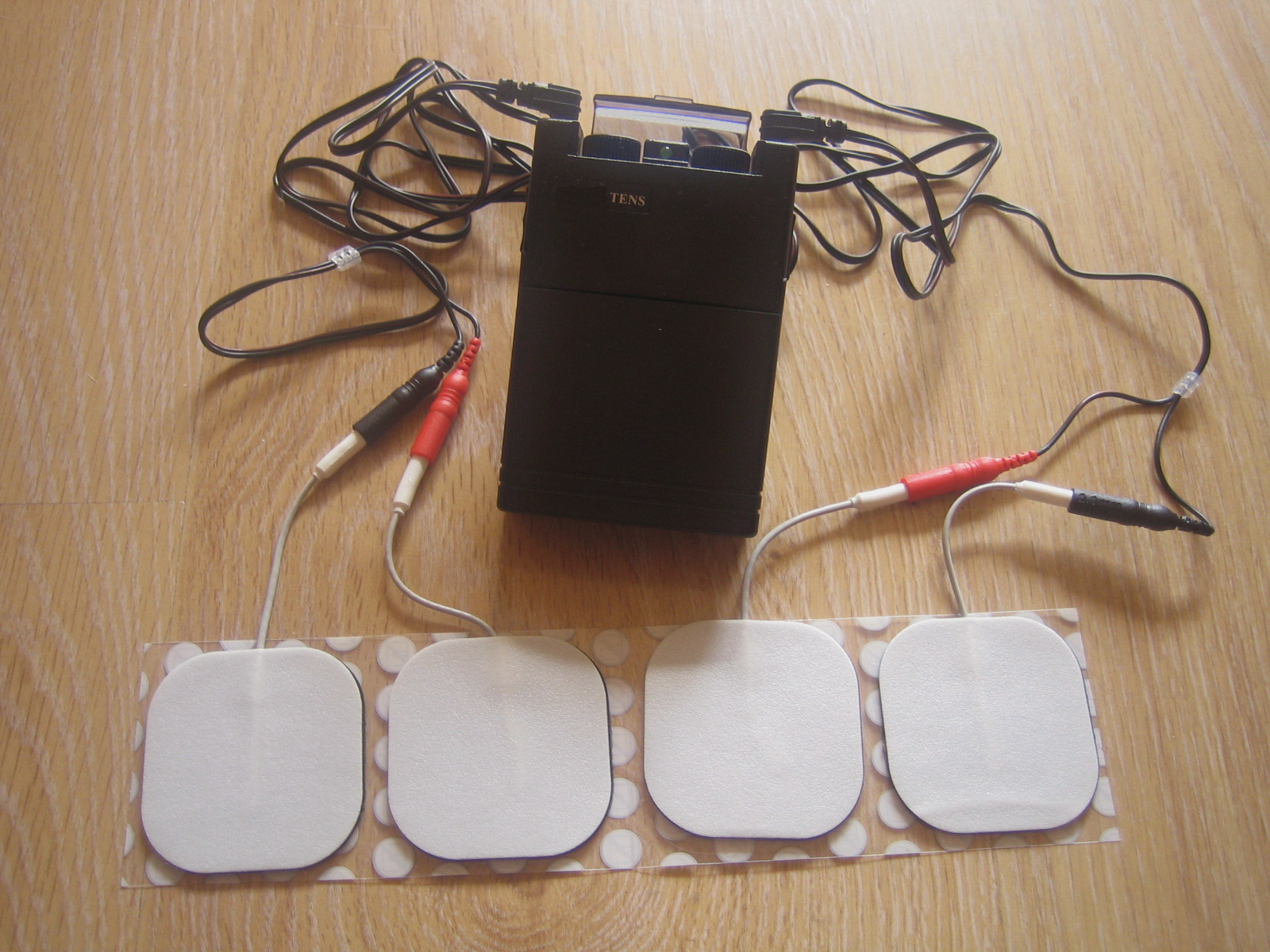

TENS stands for Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation. TENS units are devices that produce electrical currents for therapeutic purposes, usually for pain relief. They are used in physical therapy clinics, and there are many brands of portable stimulators for home use. These are typically battery-powered and have electrodes that attach to the skin with gel pads. The evidence is mixed. There are positive clinical studies but also negative studies and there is controversy over when to use TENS and what settings to use. It is not the treatment of first choice for any condition.

In ancient history electric fish and eels were reportedly used to relieve pain, but that was before anyone understood what electricity was. Development of today’s TENS device is attributed to a 20th century American neurosurgeon. It has been used to treat many conditions, including acute and chronic pain from temporomandibular joint dysfunction, migraine, postoperative pain, childbirth, dysmenorrhea, cancer, knee osteoarthritis, diabetic neuropathy, phantom limb syndrome, muscle knots, endometriosis, multiple sclerosis, injuries, fibromyalgia, and carpal tunnel.

TENS units have also been used for erotic stimulation. No comment.

How does it work?

It works by both peripheral and central mechanisms. It was found to release endogenous opioids in the brain, but endogenous opioid release has also been implicated in the placebo response. The duration of pain relief may be up to 24 hours, but for some patients the pain returns as soon as they switch off the device.

Contraindications and safety

Pregnancy, epilepsy, heart problems, and pacemakers are generally considered contraindications, although it is used in pregnancy to treat labor pains. TENS is generally safe, although contact dermatitis and allergic reactions have been reported, as have fainting and nausea. They recommend not using TENS units while driving or operating heavy equipment. Habituation might lead to reduced effectiveness or even to increased pain. Applying the electrodes to some locations is contraindicated: over the eyes, transcerebrally, on the front of the neck, internally, on broken skin and wounds, through the chest, over the spinal cord, and over a tumor.

What does the evidence show?

There have been many studies of TENS for treating various kinds of pain, and there have been many systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Numerous organizations have reviewed the evidence and issued statements. I can’t cover them all here, but I’ll provide some examples to give you a sense of the scope of the evidence.

Medical News Today said “Due to a lack of high-quality research and clinical trials, researchers have not yet determined whether TENS is a reliable treatment for pain relief”.

The American Academy of Neurology issued guidelines saying TENS is not recommended for chronic low back pain because research shows it is not effective. They also commented that TENS can be effective in treating diabetic nerve pain, but said more research is needed.

Medicare covers part of the cost of rental of TENS units for acute post-operative care for up to 30 days, and purchase of TENS units for chronic pain lasting at least 3 months. It must be medically necessary and prescribed by an authorized provider.

Aetna considers it experimental and investigational for most conditions, and will only pay for its use in acute postoperative pain and certain types of chronic, intractable pain.

A 2014 review found inconsistent evidence but concluded “Systematic reviews suggest that TENS, when applied at adequate intensities, is effective for postoperative pain, osteoarthritis, painful diabetic neuropathy and some acute pain conditions”.

A 2020 study found TENS superior to placebo for postoperative pain relief.

A 2020 meta-analysis based on four studies found TENS somewhat effective for tinnitus.

A Cochrane review found conflicting effects of TENS for the pain of rheumatoid arthritis.

Another Cochrane review was unable to assess the effectiveness of TENS for phantom limb pain and stump pain because they found no randomized controlled trials to evaluate. A 2015 Cochrane update found “tentative evidence” that TENS was superior to placebo for acute pain, but found that the studies had high risk of bias and there was incomplete reporting.

A 2018 meta-analysis of 12 RCTs concluded “These results suggest that TENS does not improve symptoms of lower back pain, but may offer short-term improvement of functional disability”.

In PainScience, Paul Ingraham reviewed the evidence for TENS and found that the systematic reviews were mostly negative or inconclusive. He concluded:

it probably mostly doesn’t work much better for most pain than an aspirin, and it’s not much good for anything else except maybe some relaxation or gently exercising muscles in rehab…it probably works well enough for some patients to be worth trying if you’re desperate…but keep your expectations low

He considers it a form of sensation-enhanced placebo.

Conclusion: Inconclusive evidence

I have to agree with Paul Ingraham that there is some evidence for using TENS for some pain conditions, but that it doesn’t appear to be very effective for anything else.

I agree that it may be worth trying for patients who are desperate, but they should keep their expectations low. Or they could try standing on an electric fish, as reportedly used in ancient times. TENS is undoubtedly more convenient than electric fish, although it would not be as acceptable to those who want “natural” remedies.